URL shortening has evolved into one of the main practices for the easy dissemination and sharing of URLs. URL shortening services provide their users with a smaller equivalent of any provided long URL, and redirect subsequent visitors to the intended source.

Why do we need URL shortening?

URL shortening is used to create shorter aliases for long URLs. We call these shortened aliases “short links.” Users are redirected to the original URL when they hit these short links. Short links save a lot of space when displayed, printed, messaged, or tweeted. Additionally, users are less likely to mistype shorter URLs. For example, if we shorten the following URL through TinyURL:

https://dsc-vjti.github.io/a-z-cloud/docs/l/cloud-load-balancing/

We would get:

The shortened URL is nearly one-third the size of the actual URL.

System Design goals

Functional Requirements:

- Given a URL, our service should generate a shorter and unique alias of it. This is called a short link. This link should be short enough to be easily copied and pasted into applications.

- When users access a short link, our service should redirect them to the original link.

- Users should optionally be able to pick a custom short link for their URL.

- Links will expire after a standard default timespan. Users should be able to specify the expiration time.

Non-Functional Requirements:

- The system should be highly available. This is required because, if our service is down, all the URL redirections will start failing.

- URL redirection should happen in real-time with minimal latency.

- Shortened links should not be guessable (not predictable).

Traffic and System Capacity

Traffic

Assuming 200:1 read/write ratio,

Number of unique shortened links generated per month = 100 million

Number of unique shortened links generated per seconds = 100 million /(30 days * 24 hours * 3600 seconds ) ~ 40 URLs/second

With 200:1 read/write ratio, number of redirections = 40 URLs/s * 200 = 8000 URLs/s

Storage

Assuming lifetime of service to be 100 years and with 100 million shortened links creation per month, total number of data points/objects in system will be = 100 million/month * 100 (years) * 12 (months) = 120 billion

Assuming size of each data object (Short url, long url, created date etc.) to be 500 bytes long, then total require storage = 120 billion * 500 bytes =60TB

Memory

Following Pareto Principle, better known as the 80:20 rule for caching. (80% requests are for 20% data)

Since we get 8000 read/redirection requests per second, we will be getting 700 million requests per day:

8000/s * 86400 seconds =~700 million

To cache 20% of these requests, we will need ~70GB of memory.

0.2 * 700 million * 500 bytes = ~70GB

High Level Design

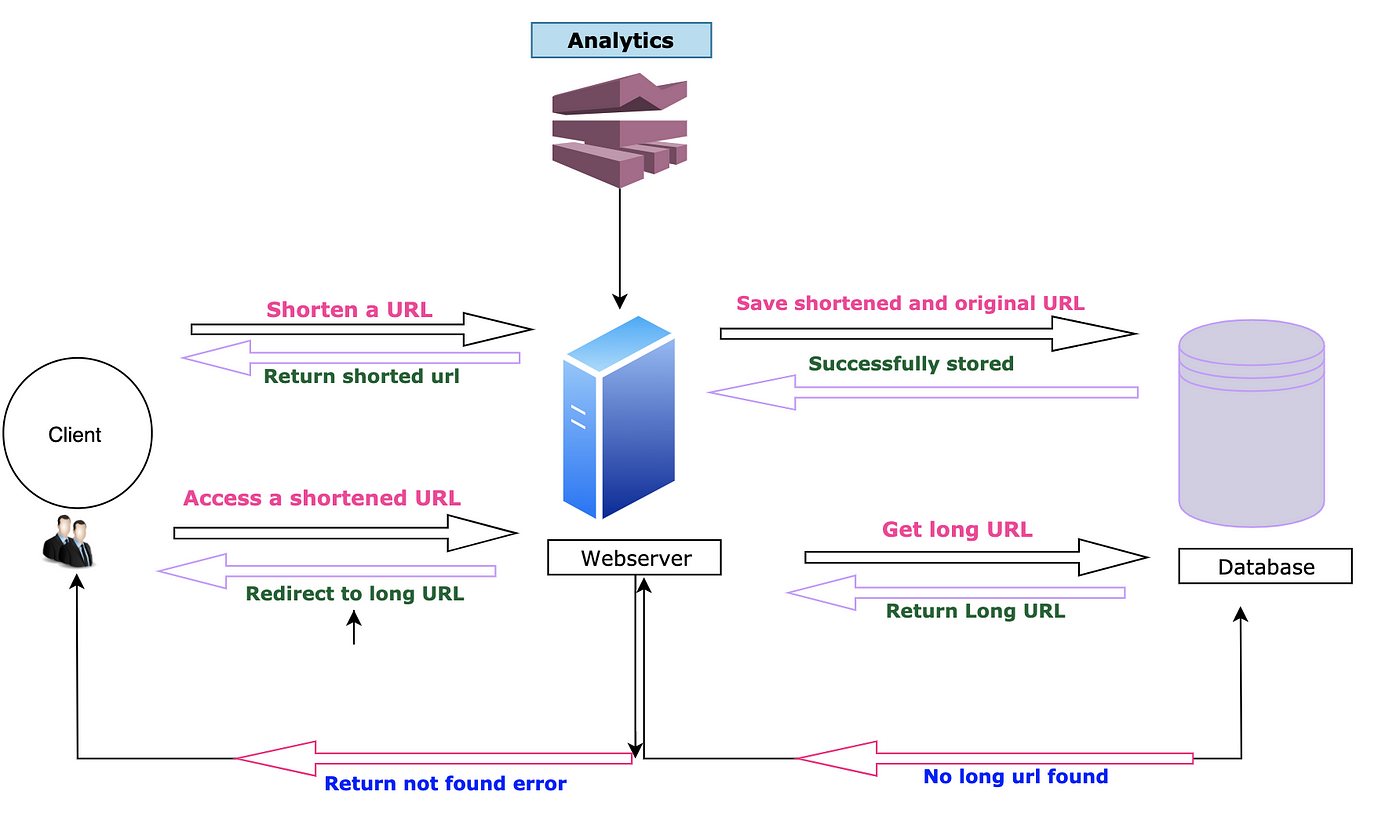

Following is high level design of our URL service. This is a rudimentary design which needs to be optimized.

A Rudimentary design for URL service

Problems with above design :

- There is only one WebServer which is single point of failure (SPOF)

- System is not scalable

- There is only single database which might not be sufficient for 60 TB of storage and high load of 8000/s read requests

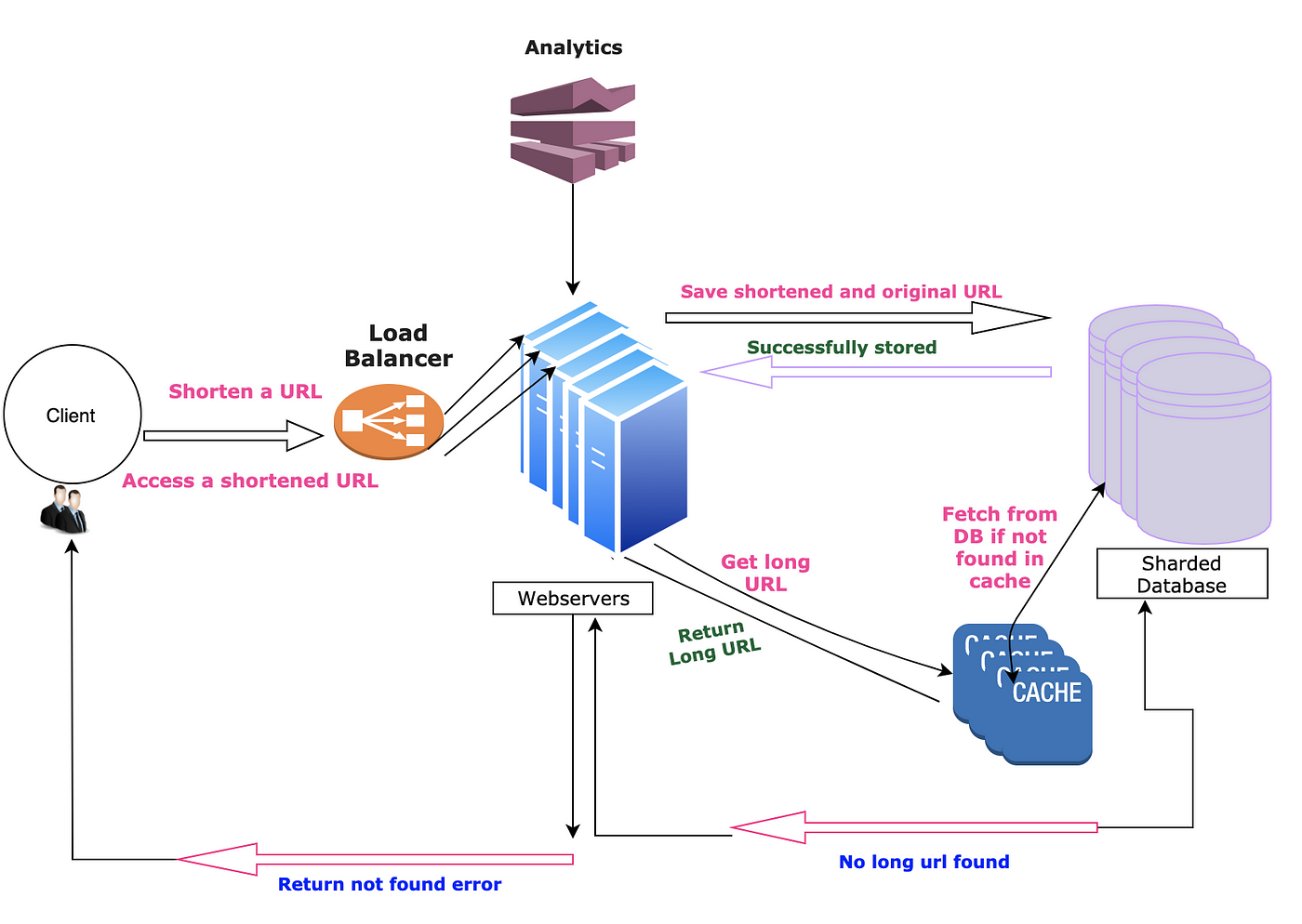

To cater to the above limitations we:

- Added a load balancer in front of WebServers

- Sharded the database to handle huge object data

- Added cache system to reduce load on the database.

Scalable high level design

REST Endpoints

Let’s starts by making two functions accessible through REST API:

create( long_url, api_key, custom_url)

POST

Tinyrl : POST :https://tinyurl.com/app/api/create

Request Body: {url=long_url}

Return OK (200), with the generated short_url in data.

long_url: A long URL that needs to be shortened.

api_key: A unique API key provided to each user, to protect from the spammers, access, and resource control for the user, etc.

custom_url(optional): The custom short link URL, user want to use.

Return Value: The short Url generated, or error code in case of the inappropriate parameter.

GET: /{short_url}

Return a http redirect response(302)

Note : “HTTP 302 Redirect” status is sent back to the browser instead of “HTTP 301 Redirect”. A 301 redirect means that the page has permanently moved to a new location. A 302 redirect means that the move is only temporary. Thus, returning 302 redirect will ensure all requests for redirection reaches to our backend and we can perform analytics (Which is a functional requirement)

short_url: The short URL generated from the above function.

Return Value: The original long URL, or invalid URL error code.

Database Schema

Let’s see the data we need to store: Data Related to user

- User ID: A unique user id or API key to make user globally distinguishable

- Name: The name of the user

- Email: The email id of the user

- Creation Date: The date on which the user was registered

Data Related to ShortLink

- Short Url: 6/7 character long unique short URL

- Original Url: The original long URL

- UserId: The unique user id or API key of the user who created the short URL

Shortening Algorithm

For shortening a url we can use following two solutions (URL encoding and Key Generation service). Let’s walk through each of them one by one.

- URL Encoding

a. URL encoding through base62

b. URL encoding through MD5 - Key Generation Service (KGS)

URL encoding through base62 A base is a number of digits or characters that can be used to represent a particular number. Base 10 are digits [0–9], which we use in everyday life and base 62 are [0–9][a-z][A-Z] Let’s do a back of the envelope calculation to find out how many characters shall we keep in our tiny url.

URL with length 5, will give 62⁵ = ~916 Million URLs

URL with length 6, will give 62⁶ = ~56 Billion URLs

URL with length 7, will give 62⁷ = ~3500 Billion URLs

Since we required to produce 120 billion URLs, with 7 characters in base62 we will get ~3500 Billion URLs. Hence each of tiny url generated will have 7 characters.

How to get unique ‘7 character’ long random URLs in base62?

Once we have decided number of characters to use in Tiny URL (7 characters) and also the base to use (base 62 [0–9][a-z][A-Z] ), then the next challenge is how to generate unique URLs which are 7 characters long.

Technique 1 — Short url from random numbers:

We could just make a random choice for each character and check if this tiny url exists in DB or not. If it doesn’t exist return the tiny url else continue rolling/retrying.As more and more 7 characters short links are generated in Database, we would require 4 rolls before finding non-existing one short link which will slow down tiny url generation process.

Technique 2 — Short urls from base conversion:

Think of the seven-bit short url as a hexadecimal number (0–9, a-z, A-Z) (For e.g. aKc3K4b) . Each short url can be mapped to a decimal integer by using base conversion and vice versa.

How do we do the base conversion? This is easiest to show by an example.

Take the number 125 in base 10.

It has a 1 in the 100s place, a 2 in the 10s place, and a 5 in the 1s place. In general, the places in a base-10 number are:

- 10⁰

- 10¹

- 10²

- 10³

- etc.

The places in a base-62 number are:

- 62⁰

- 62¹

- 62²=3,844

- 62³=238,328

- etc.

So to convert 125 to base-62, we distribute that 125 across these base-62 “places”. The highest “place” that can take some is 62¹, which is 62. 125/62 is 2, with a remainder of 1. So we put a 2 in the 62’s place and a 1 in the 1’s place. So our answer is 21. What about a higher number — say, 7,912? Now we have enough to put something in the 3,844’s place (the 62²’s place). 7,912 / 3,844 is 2 with a remainder of 224. So we put a 2 in the 3,844’s place, and we distribute that remaining 224 across the remaining places — the 62’s place and the 1’s place. 224 / 62 is 3 with a remainder of 38. So we put a 3 in the 62’s place and a 38 in the 1’s place. We have this three-digit number: 23- 38. Now, that “38” represents one numeral in our base-62 number. So we need to convert that 38 into a specific choice from our set of numerals: a-z, A-Z, and 0–9.

Let’s number each of our 62 numerals, like so:

0: 0,

1: 1,

2: 2,

3: 3,

...

10: a,

11: b,

12: c,

...

36: A,

37: B,

38: C,

...

61: Z

As you can see, our “38th” numeral is “C.” So we convert that 38 to a “C.” That gives us 23C. So we can start with a counter (A Large number 100000000000 in base 10 which 1L9zO9O in base 62) and increment counter every-time we get request for new short url (100000000001, 100000000002, 100000000003 etc.) .This way we will always get a unique short url.

100000000000 (Base 10) ==> 1L9zO9O (Base 62)

Similarly, when we get tiny url link for redirection we can convert this base62 tiny url to a integer in base10

1L9zO9O (Base 62) ==>100000000000 (Base 10)

Technique 3 — MD5 hash:

The MD5 message-digest algorithm is a widely used hash function producing a 128-bit hash value(or 32 hexadecimal digits). We can use these 32 hexadecimal digit for generating 7 characters long tiny url.

- Encode the long URL using the MD5 algorithm and take only the first 7 characters to generate TinyURL.

- The first 7 characters could be the same for different long URLs so check the DB to verify that TinyURL is not used already

- Try next 7 characters of previous choice of 7 characters already exist in DB and continue until you find a unique value.

With all these shortening algorithms, let’s revisit our design goals!

- Being able to store a lot of short links (120 billion)

- Our TinyURL should be as short as possible (7 characters)

- Application should be resilient to load spikes (For both url redirections and short link generation)

- Following a short link should be fast.

All the above techniques we discussed above will help us in achieving goal (1) and (2). But will fail at step (3) and step (4). Let’s see how.

- A single web-server is a single point of failure (SPOF). If this web-server goes down, none of our users will be able to generate tiny urls/or access original (long) urls from tiny urls. This can be handled by adding more web-servers for redundancy and then bringing a load balancer in front but even with this design choice next challenge will come from database

- With database we have two options : a. Relational databases (RDBMs) like MySQL and Postgres b. “NoSQL”-style databases like BigTable and Cassandra

If we choose RDBMs as our database to store the data then it is efficient to check if an URL exists in database and handle concurrent writes. But RDBMs are difficult to scale (We will use RDBMS for scaling in one of our Technique and will see how to scale using RDBMS)

If we opt for “NOSQL”, we can leverage scaling power of “NOSQL”-style databases but these systems are eventually consistent (Unlike RDBMs which provides ACID consistency).

We can use putIfAbsent(TinyURL, long URL) or INSERT-IF-NOT-EXIST condition while inserting the tiny URL but this requires support from DB which is available in RDBMS but not in NoSQL. Data is eventually consistent in NoSQL so putIfAbsent feature support might not be available in the NoSQL database(We can handle this using some of the features of NOSQL which we have discussed later on in this article). This can cause consistency issue (Two different long URLs having the same tiny url).

Scaling Technique 1 — Short url from random numbers We can use a relational database as our backend store but since we don’t have joins between objects and we require huge storage size (60TB) along with high writes (40 URL’s per seconds) and read (8000/s) speed, a NoSQL store (MongoDB, Cassandra etc.) will be better choice. We can certainly scale using SQL (By using custom partitioning and replication which is by default available in MongoDB and Cassandra) but this difficult to develop and maintain.

Let’s discuss how to use MongoDB to scale database for shortening algorithm given in Technique — 1 MongoDB supports distributing data across multiple machines using shards. Since we have to support large data sets and high throughput, we can leverage sharding feature of MongoDB.

Once we generate 7 characters long tiny url, we can use this tinyURL as shard key and employ sharding strategy as hashed sharding. MongoDB automatically computes the hashes (Using tiny url ) when resolving queries. Applications do not need to compute hashes. Data distribution based on hashed values facilitates more even data distribution, especially in data sets where the shard key changes monotonically.

We can scale reads/writes by increasing number of shards for our collection containing tinyURL data(Schema having three fields Short Url,Original Url,UserId). Schema for collection tiny URL :

{

_id: <ObjectId102>,

shortUrl: "https://tinyurl.com/3sh2ps6v",

originalUrl: "https://medium.com/@sandeep4.verma",

userId: "sandeepv",

}

Since MongoDB supports transaction for a single document, we can maintain consistency and because we are using hash based shard key, we can efficiently use putIfAbsent (As a hash will always be corresponding to a shard).

To speed up reads (checking whether a Short URL exists in DB or what is Original url corresponding to a short URL) we can create indexing on ShortURL.

We will also use cache to further speed up reads.

Scaling Technique 2 — Short urls from base conversion We used a counter (A large number) and then converted it into a base62 7 character tinyURL.As counters always get incremented so we can get a new value for every new request (Thus we don’t need to worry about getting same tinyURL for different long/original urls).

Scaling with SQL sharding and auto increment

Sharding is a scale-out approach in which database tables are partitioned, and each partition is put on a separate RDBMS server. For SQL, this means each node has its own separate SQL RDBMS managing its own separate set of data partitions. This data separation allows the application to distribute queries across multiple servers simultaneously, creating parallelism and thus increasing the scale of that workload. However, this data and server separation also creates challenges, including sharding key choice, schema design, and application rewrites. Additional challenges of sharding MySQL include data maintenance, infrastructure maintenance, and business challenges.

Before an RDBMS can be sharded, several design decisions must be made. Each of these is critical to both the performance of the sharded array, as well as the flexibility of the implementation going forward. These design decisions include the following:

- Sharding key must be chosen.

- Schema changes.

- Mapping between sharding key, shards (databases), and physical servers.

We can use sharding key as auto-incrementing counter and divide them into ranges for example from 1 to 10M, server 2 ranges from 10M to 20M, and so on. We can start the counter from 100000000000. So counter for each SQL database instance will be in range 100000000000+1 to 100000000000+10M , 100000000000+10M to 100000000000+20M and so on. We can start with 100 database instances and as and when any instance reaches maximum limit (10M), we can stop saving objects there and spin up a new server instance. In case one instance is not available/or down or when we require high throughput for write we can spawn multiple new server instances. Schema for collection tiny URL For RDBMS :

CREATE TABLE tinyUrl (

id BIGINT NOT NULL, AUTO_INCREMENT

shortUrl VARCHAR(7) NOT NULL,

originalUrl VARCHAR(400) NOT NULL,

userId VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

automatically on primary-key column

-- INDEX (shortUrl)

-- INDEX (originalUrl)

);

Where to keep which information about active database instances?

We can use a distributed service Zookeeper to solve the various challenges of a distributed system like a race condition, deadlock, or particle failure of data. Zookeeper is basically a distributed coordination service that manages a large set of hosts. It keeps track of all the things such as the naming of the servers, active database servers, dead servers, configuration information (Which server is managing which range of counters)of all the hosts. It provides coordination and maintains the synchronization between the multiple servers.

How to check whether short URL is present in database or not?

When we get tiny url (For example 1L9zO9O) we can use base62ToBase10 function to get the counter value (100000000000). Once we have this values we can get which database this counter ranges belongs to from zookeeper(Let’s say it database instance 1 ) . Then we can send SQL query to this server (Select * from tinyUrl where id=10000000000111).This will provide us sql row data (*if present)

How to get original url corresponding to tiny url?

We can leverage the above solution to get back the sql row data. This data will have shortUrl, originalURL and userId.

Scaling Technique 3— MD5 hash

We can leverage the scaling Technique 1 (Using MongoDB). We can also use Cassandra in place of MongoDB. In Cassandra instead of using shard key we will use partition key to distribute our data.

Technique 4 — Key Generation Service (KGS)

We can have a standalone Key Generation Service (KGS) that generates random seven-letter strings beforehand and stores them in a database (let’s call it key-DB). Whenever we want to shorten a URL, we will take one of the already-generated keys and use it. This approach will make things quite simple and fast. Not only are we not encoding the URL, but we won’t have to worry about duplications or collisions. KGS will make sure all the keys inserted into key-DB are unique.

Can concurrency cause problems? As soon as a key is used, it should be marked in the database to ensure that it is not used again. If there are multiple servers reading keys concurrently, we might get a scenario where two or more servers try to read the same key from the database. How can we solve this concurrency problem? Servers can use KGS to read/mark keys in the database. KGS can use two tables to store keys: one for keys that are not used yet, and one for all the used keys. As soon as KGS gives keys to one of the servers, it can move them to the used keys table. KGS can always keep some keys in memory to quickly provide them whenever a server needs them. For simplicity, as soon as KGS loads some keys in memory, it can move them to the used keys table. This ensures each server gets unique keys. If KGS dies before assigning all the loaded keys to some server, we will be wasting those keys–which could be acceptable, given the huge number of keys we have. KGS also has to make sure not to give the same key to multiple servers. For that, it must synchronize (or get a lock on) the data structure holding the keys before removing keys from it and giving them to a server.

Isn’t KGS a single point of failure?

Yes, it is. To solve this, we can have a standby replica of KGS. Whenever the primary server dies, the standby server can take over to generate and provide keys.

Can each app server cache some keys from key-DB?

Yes, this can surely speed things up. Although, in this case, if the application server dies before consuming all the keys, we will end up losing those keys. This can be acceptable since we have 68B unique six-letter keys.

How would we perform a key lookup?

We can look up the key in our database to get the full URL. If its present in the DB, issue an “HTTP 302 Redirect” status back to the browser, passing the stored URL in the “Location” field of the request. If that key is not present in our system, issue an “HTTP 404 Not Found” status or redirect the user back to the homepage.

Should we impose size limits on custom aliases? Our service supports custom aliases. Users can pick any ‘key’ they like, but providing a custom alias is not mandatory. However, it is reasonable (and often desirable) to impose a size limit on a custom alias to ensure we have a consistent URL database. Let’s assume users can specify a maximum of 16 characters per customer key.

Cache

We can cache URLs that are frequently accessed. We can use some off-the-shelf solution like Memcached, which can store full URLs with their respective hashes. Before hitting backend storage, the application servers can quickly check if the cache has the desired URL.

How much cache memory should we have?

We can start with 20% of daily traffic and, based on clients’ usage patterns, we can adjust how many cache servers we need. As estimated above, we need 70GB memory to cache 20% of daily traffic. Since a modern-day server can have 256GB memory, we can easily fit all the cache into one machine. Alternatively, we can use a couple of smaller servers to store all these hot URLs.

Which cache eviction policy would best fit our needs?

When the cache is full, and we want to replace a link with a newer/hotter URL, how would we choose? Least Recently Used (LRU) can be a reasonable policy for our system. Under this policy, we discard the least recently used URL first. We can use a Linked Hash Map or a similar data structure to store our URLs and Hashes, which will also keep track of the URLs that have been accessed recently.

To further increase the efficiency, we can replicate our caching servers to distribute the load between them.

How can each cache replica be updated?

Whenever there is a cache miss, our servers would be hitting a backend database. Whenever this happens, we can update the cache and pass the new entry to all the cache replicas. Each replica can update its cache by adding the new entry. If a replica already has that entry, it can simply ignore it.

Load Balancer (LB)

We can add a Load balancing layer at three places in our system:

- Between Clients and Application servers.

- Between Application Servers and database servers.

- Between Application Servers and Cache servers.

Initially, we could use a simple Round Robin approach that distributes incoming requests equally among backend servers. This LB is simple to implement and does not introduce any overhead. Another benefit of this approach is that if a server is dead, LB will take it out of the rotation and will stop sending any traffic to it.

A problem with Round Robin LB is that we don’t take the server load into consideration. If a server is overloaded or slow, the LB will not stop sending new requests to that server. To handle this, a more intelligent LB solution can be placed that periodically queries the backend server about its load and adjusts traffic based on that.

Customer provided tiny URLs

A customer can also provide a tiny url of his/her choice. We can allow customer to choose just alphanumerics and the “special characters” $-_.+!*’(),. in tiny url(With let’s say 8 minimum characters). When customer provides a custom url we can save it to some other instance of database (Different one from where system generates tiny url against original url) and treat these tiny URLs as special URLs. When we get redirection request we can divert these request to special instances of WebServer . Since this will be a paid service we can expect very few tiny URLs to be of this kind and we don’t need to worry about scaling WebServers/Database in this case.

Analytics

How many times has a short URL been used ? How should we store these statistics? Since we used “HTTP 302 Redirect” status to the browser instead of “HTTP 301 Redirect”, thus each redirection for tiny url will reach service’s backend. We can push this data(tiny url, users etc.) to a Kafka queue and perform analytics in real time.

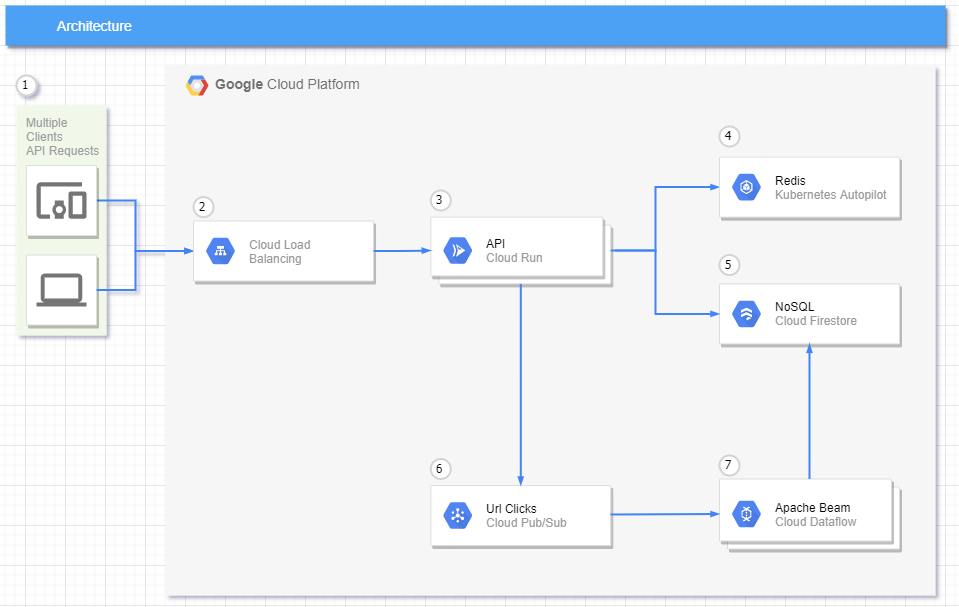

How does GCP support such a URL shortener service?

url-shortener is a small API that provides basic REST endpoints to shorten a URL, get information about the URL, update the URL, and get statistics on most accessed URLs.

The technology behind it:

- Golang 1.17

- Gin Web Framework

- Google Firestore

- Google PubSub

- Redis

- NanoID

- Swagger

Architecture

Written in Hexagonal Architecture

- Requests can come from many types of devices.

- Cloud Run is a fully managed serverless platform which already has an integrated load balance.

- Cloud Run will automatically scale to the number of container instances needed to handle all incoming requests.

- All request to get a URL will be checked in the cache first and any new URL that is generated will cached with a configurable TTL.

- All request to get a URL that is not found in the cache will be queried on the NoSQL and any new URL that is generated will be stored on the NoSQL.

- For each redirect request, a message will be sent to a pubsub topic to record that we had one more access.

- Here, we have an Apache Beam pipeline running in Dataflow, to group all messages by Id in a fixed time window, that will update the NoSQL database.